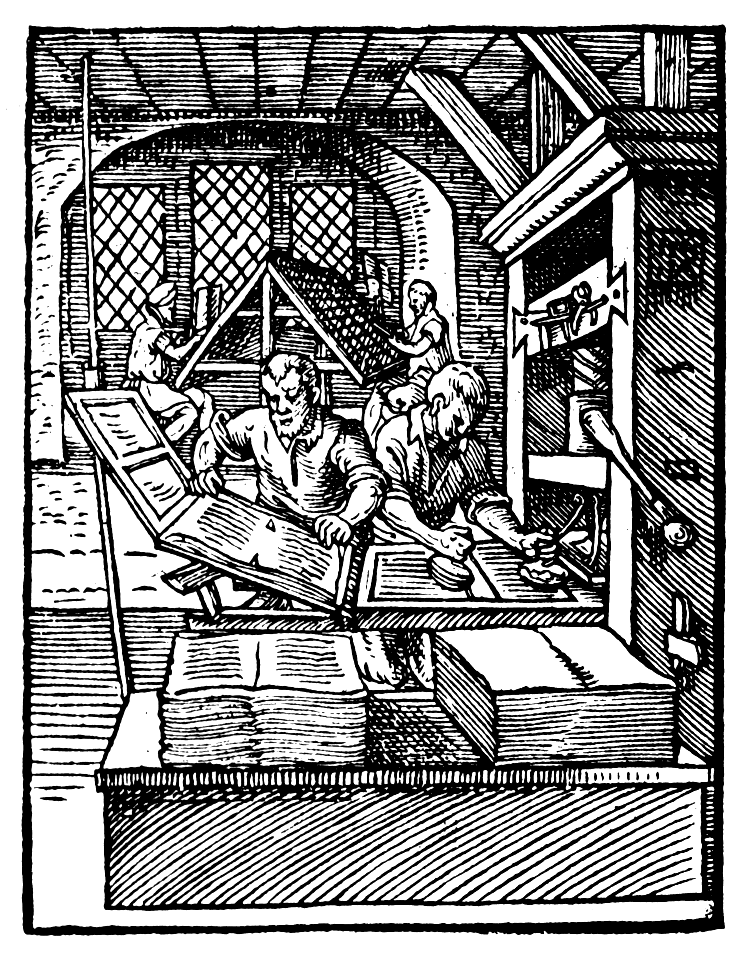

Was Gutenberg really the first?

Look at any high school history textbook and it will tell you what everyone has known for centuries: Gutenberg invented the movable type printing press. Here’s what Wikipedia, the Google scholar’s oracle, has to say:

Johannes Gensfleish zur Laden zum Gutenberg (c. 1400- 3 February 1468) was a German inventor, printer, publisher, and goldsmith who introduced printing to Europe with his mechanical movable-type printing press

Even popular blogsites specializing in the history of printing and type, such as www.designhistory.org, devote entire articles to this fact, complete with (out-of-date) scholarly sources.

The problem is, it’s not true. Around 1470, someone in the Netherlands or Germany did invent modern, movable type. But by then Gutenberg was dead.

Measuring a bull

So who figured out that Gutenberg hadn’t invented movable type and how did they know?

Before he invented Seadragon and its visual optimization system which made streaming movies on Netflix possible, before Photosynth, and especially his Arts and Machine intelligence program, and before his TED talks – among the best ever – Blaise Agüera y Arcas was a student at Princeton majoring in physics. In 2001, working with rare books librarian Paul Needham, Agüera y Arcas imaged a Papal Bull issued by the Vatican in 1456 and printed by Gutenberg as well as a Gutenberg Bible from 1455, both in the Princeton’s rare books collection. Using software he developed, Agüera y Arcas measured the dimensions of every single letter “i” and found hundreds of different variations. That meant that the individual pieces of type were not mass produced using the so-called “punch and matrix” system which experts say defines mechanical moveable type.

Punch matrix

The claim against Gutenberg depends on a technical definition of what movable type really is. After all, the Chinese had used clay type for their printing for over a thousand years, and in the 13th century, the Koreans developed a method for casting metal type in sand molds. The problem with these methods, some scholars argue, was that when the pieces of type wore out, they had to make new molds to make new pieces of type. This made printing labor intensive and not practical, while the individual pieces of type varied from one book to the next.

Punch and matrix system

Punch and matrix system

The punch and matrix was a defining leap forward in efficiency in printing technology. In an interview in 2001, Paul Needham explained how it worked:

You engrave the steel punch with a character on its end, then use the punch to strike a character in a matrix – a block of [softer] copper. You pour the type metal, a lead alloy, into it. The resulting letters all look alike because they’ve come from the same mold, the same matrix, and ultimately from the same punch. It really is mass production as we think of it today

But the fact that Gutenberg’s letters showed many different and unique varieties means, therefore, he must have been using something other than a punch and matrix, probably a method like the Korean sand casting.

The next chapter: RTI

Agüera y Arcas’s use of digital imaging demonstrates how much we can learn by applying scientific analysis to documents. But is there more to be learned from Gutenberg’s printing method by imaging his early early printed books? At the University of Southen California, Professor Bruce Zuckerman, a specialist in the Bible, was among the first to use an imaging technique called Reflectance Transformation Imaging (or Polynomial Texture Mapping) on objects and documents to reveal difficult to see details.

Single lighting position for RTI

Single lighting position for RTI

In RTI, an object is photographed multiple times with the light source placed in various positions in a hemisphere around the object. The purpose is to capture the shadows cast by small, topographical details from every perspective and to combine them into a single “texture map” of the object’s surface. The result is an image with every feature in fine relief that looks a bit like Han Solo after Jabba the Hut freezes him in carbonite.

Zuckerman has collected thousands of RTI images of biblical objects in a database called Inscriptifact (http://www.inscriptifact.com/index.shtml) which is freely searchable. One of those images, of a Gutenberg Bible, raises some interesting questions about Gutenberg’s printing process.

Notice the “U” in “Utinam.” It has a typical red decoration called a pied de mouche. How did it get there? Scholars have maintained that the pieds de mouche in Gutenberg’s Bibles were painted on by hand after printing. But from the RTI image, it is clear that they were quite clearly printed on the page beforehand, and the capital letter was then printed over it. This raises the question of how Gutenberg managed to align two different plates, one with decorations and the other with type. Using Agüera y Arcas’s measurement techniques, further examination of other Gutenberg Bibles should show whether the alignment of all the “U"s is exactly the same. This would require that his press had some mechanical way to repeat this method.